Last Week, we published photographs from Memory Trace, which is part of Fazal Sheikh’s magnificent Erasure Trilogy about the attempted erasure of Palestinian history and life after the Nakba. We said we would publish reflections about photographs from Erasure that were first shared at Storefront for Art and Architecture in 2016, where Fazal’s photographs were on display at Storefront’s gallery space. At this inspiring gathering, scholars and artists, Emmet Gowin, Amira Hass, Rashid Khalidi, Rosalind Morris, Shela Sheikh, Michael Wood and Sadia Abbas were each asked to speak about an image from the trilogy. Some spoke extemporaneously and some—like Rosalind, Shela, and Sadia — read from texts we had written. Rosalind chose an image from Desert Bloom and Shela from Independence/Nakba. We reached out to Rosalind and Shela to ask them if they would share their wonderful meditations with our readers, and they generously agreed. Over the next days, we will put up Shela’s, Rosalind’s, and Sadia’s responses. Here is the first:

Remarks by Rosalind Morris on a photographic image by Fazal Sheikh.

These remarks were first penned for the occasion of an opening of Fazal Sheikh’s work, curated by Eduardo Cadava at the Storefront for Art and Architecture on April 20, 2016. I have not altered these words, which seem to me today to retain the sense provoked in me by the particular photograph to which I was invited to respond then. That image has remained with me in the tumultuous years since, not only as a memory trace but as a persistent challenge to look more carefully, more closely, more questioningly at that which comes into view from afar.

Let me then begin. I have chosen to speak about #15 in the series Desert Bloom.

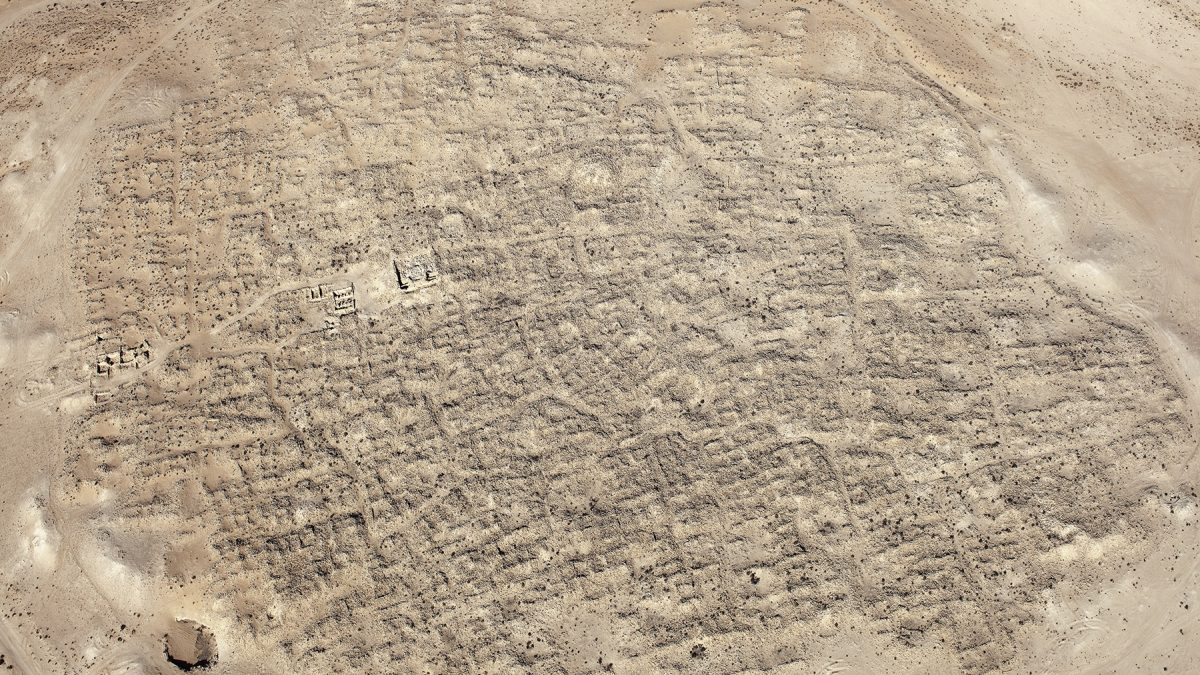

How shall I describe this image? An allegory tempts me, thanks to the ghostly trace of a human skull that seems to emerge, mirage-like at the periphery of the settlement whose destruction provides the historical background for this image. But to indulge that conjuration would be to leave the photograph behind, and this is, above all, a photograph.

The photograph, I wish to assert, says nothing. Tells me nothing. Proves nothing. And yet, if it is mute, it is not silent or at least it seems to bid a response. Questions gather there, where the grain of the photograph and the grain that is sand coalesce. Medium and referent fold over on each other in this and many other images that comprise the Desert Bloom volume of Fazal Sheikh’s remarkable and utterly heart-breaking trilogy. There are other images in this volume, where more certain figures can be drawn against the ground—of squat buildings, water reservoirs and agricultural activity, tented shelters with tires and metallic waste strewn across the landscape. There are also photographs of desiccated riverbeds and fire-scorched earth. Yet, even in these more resolute images of still-recognizable forms, the rubble and the sand function as both referent and figure for the dissolution of structure—that which has occurred and that which is occurring, as well as that which is anticipated on the horizon of the status quo in Israel-occupied Palestine.

The textural weave of these two levels—of referent and figure, earthly sand and photographic grain—is accomplished partly by the artifice of distance. The aerial perspective dissolves, in the manner of an acid bath, what proximity would have disclosed in more accessible detail: the line of a ruined street, the stubble of a tree no longer irrigated by human hands, the abandoned foundation of a house, a shop, a mosque, the effaced courtyard wherein coffee once was drunk. That which was here has become ruin in the decades since the Nakba. And it is the disappearing of that previous existence that is traced in these images—by virtue of distance. The profundity of ruination that is seen from the very distance that made the visual regime of modern Israeli militarism possible approaches its maximal intensity where it can no longer be read except at the level of residual contour, which is to say mere form.

Thus, if these images, and this one in particular, invite us into formalism, if we find a morbid beauty in the monochromatic surfaces, etched with shadow and abstract geometries, it is not because, as Walter Benjamin said (and Susan Sontag repeated) that we have learned to find beauty in that which is vanishing. It is rather, that the violently induced ruination of the Nakba has left us with form, rather than formlessness, as testimony to erasure. In time, perhaps, that form will be filled in with new content. Perhaps, it will surrender to formlessness, but because it has not yet done so, because there is still trace, there is the possibility of those questions with which I began.

Without reducing the interrogation to the demand for a caption, then, I ask, What am I looking at? From where? And whence do I gaze? I ask these questions despite the fact that the accumulation of photographs in Fazal Sheikh’s titled and prefaced volumes prepares the way, and despite the fact that the proscenium arch of the exhibition’s metatext has over-determined my probable reading. It would, nonetheless, be possible to imagine an image like this being produced somewhere else in the world—maybe in South Asia or some parts of West Africa, maybe in Mexico. In any case, and in addition to the referential question, I ask myself, ‘What makes me look?

Because I do look, more intensely and with a more unashamed curiosity than I permit myself with Sheikh’s human portraits—beautiful though they are. No doubt, this is an aesthetic preference on my part, a modernist predilection as much as an iconoclastic pietism. But I don’t just mean to invoke my own preference. I mean to suggest that these photographs, like all good photographs, are constantly working upon the medium of photography even as they undertake the impossible but necessary task of intervening in the discursive domain, wherein truth claims are made. As I said, the photographs produce no knowledge. Nonetheless, they provoke me in a manner that leads me to demand understanding. If I narrate this demand, it entails the translation of the question, “What am I looking at?” into “What happened there, where the photograph was made?” I remind myself: I am looking at a photograph, not the world it enframes and to which it refers. Only by moving between the two discontinuous domains can we grasp what is at stake and what is necessary to make the object (the photograph) give way to an event (the Nakba) that stretches out in time and reverberates across the socio-political field that we continue to inhabit today.

In the introductory text that prefaces the first volume of the trilogy, Fazal Sheikh describes his project: the effort to find evidence of effacement, and to find what remains, not only there, but elsewhere, in refugee camps and the other destinations that received the flood of refugees from now-deserted spaces. Desert Bloom is a monument to displacement that lacks monumentalism. This is because monumentalism assumes the self-evidence of the form but distrusts it at the same time and so retreats into literality of reference. And that is precisely what the landscape photographs mock—and it is perhaps why the death’s head cannot be forgotten entirely. We should nonetheless note a crucial difference between the portraits and the landscape photographs. The portraits are accompanied by narratives of expulsion and survival, of living after: with dates and details of the documentable life. The landscapes are accompanied by a different kind information.

Sheikh notes the significant fact that many of the towns he photographed have not only vanished into the sand that we see in image #15, but that their names have also been erased from the cartographic representations of Israeli territory. He is nonetheless able to piece together the tracery of history. He tells us that this image, produced at latitude 31°1‚48”N and longitude 34°33‚56”E, depicts the remains of Rehovot-in-the-Negev/Ruḥeiba (Heb./Arabic). His caption specifies

…during the Nabataean era, this was the second largest city along the northeast–south Nabataean spice route. The importance of the settlement was due to its location in the center of the Ḥalutza– Nitzana–Sinai trade route. In the fifth century, during the Byzantine era, the city’s population was over 10,000. The city is now located on sand dunes close to the Egyptian border and encircled by closed military live-fire training zones, operative during weekdays. At bottom left is a water pool connected to a deep well. Also visible on the left is the main access route into the town which leads to the reconstructed central square. From the ground, these are the only visible remains. The rest of the city appears like a set of haphazard topographical wrinkles. From the air, at the end of the summer, the city becomes visible under a seemingly transparent layer of earth.

These details—and they are details, strewn across the desiccated space of millennia—do not constitute the elements of a survival, as with the portraits, but are the dispersed traces of an effacement. Sheikh’s text magnifies a corner of the image, to tell us about a well and water pool, that we cannot otherwise see, and this reference to a device that once quenched the thirst of the desert is as much a scar sealing over a wound whose origin we cannot fathom as it is an explanation.

Desert Bloom – Part of The Erasure Trilogy.

In the end, this is why we must see from on high, from within the visual logic of Israeli militarism—from a plane, surveilling the earth. Sand in the machine as it were. For, it is from there that the doubling of sand and grain becomes not merely a fortuitous effect of the artist’s technology but the means for producing a displacement from one question to another. From ‘What is this?’ to ‘What happened here?’ And once again, to ‘What is happening here?’ The time of the photograph and the time of history are not identical. Unlike the photograph, history is a matter of the future.

Rosalind Morris is an award-winning anthropologist and cultural critic, who is Professor of Anthropology at Columbia University. She is the author of numerous books and essays, on topics that range from anthropology and critical social theory, to comparative literary analysis, aesthetics and the question of value. Her major field research has been in South Africa and Southeast Asia. In addition to her scholarly writings, Morris has collaborated extensively with South African artists, including William Kentridge, with whom she has written two books, Clive van den Berg, Ebrahim Hajee and Songezile Madikida. Her poetry and non-academic writings have appeared in journals like Literary Imagination, The Capilano Review, The New Ohio Review and Carapace. As a filmmaker, Rosalind Morris has directed and produced works in documentary, narrative and expanded cinematic forms. With Yvette Christiansë, she is the co-librettist on two operas with the composer Zaid Jabri.

Image credit: Fazal Sheikh, Desert Bloom–Part of The Erasure Trilogy, first edition published by Steidl in 2015.