by Patricia R. Zimmermann

In honor of the 32nd Anniversary of the American with Disabilities Act

In mid-July during the height of summer blockbuster season, the transnational commercial movie industry issued a marketing campaign and battle cry: ONLY IN THEATERS.

The industry trade magazine Variety pointed out that the pandemic saw a “murky” delineation between streaming and theatrical release, with day-and-date dominating. Day-and-date means a film drops on a streaming service the same day it opens in theaters. Black Widow (2021) released theatrically and on Disney +. Matrix Resurrection (2021) in cinemas and HBO Max. Theatrical windows shortened from 90 days to 45. But this summer in the continuing but amorphous pandemic would be different. A line would be drawn. Consumers would be enticed back to multiplexes.

“Only in theaters” was a call to arms in the struggle between the old world of analog and embodied experiences and the new world of digital streaming and films on demand operating in different galaxies. It’s open warfare between the vestiges of the old studio system in transnational conglomerates like Paramount and Disney, and new entities coming from the tech world like Netflix and Amazon. While transnational media distribution wings and theaters repeat the incantation ONLY IN THEATERS, the tech world behemoths answer with: MEDIA ANYTIME, ANYWHERE, ON ANY DEVICE AVAILABLE.

Netflix released films like Roma (2018), The Power of the Dog (2021), and Marriage Story (2019) theatrically as a marketing ploy to secure Oscar nominations with extended runs on big screens. As Anne Thompson points out in Indiewire, Netflix is now Hollywood’s “most prolific content producer.” The Russo Brothers, directors of Gray Man (2022) now streaming on Netflix, derided the streaming vs. theater debate as well as the 1970s cult of the auteur in Indiewire. “A thing to remember, too, is it’s an elitist notion to be able to go to a theater,” they argued. “So, this idea that was created—that we hang on to, that—that the theater is a sacred space, is bullshit. And it rejects the idea of allowing everyone in under the tent.”

Let’s broaden the scope a bit. This corporate marketing slogan “only in theaters” sidelines the complex histories and experiences of movie theaters that tell a different story of sharing space with others, letting a large screen engulf you, and putting yourself somewhere else, in other worlds beyond the one you live in.

Oswego

On July 5, my partner Stewart and I decided that the stormy day on Lake Ontario meant trading our jib lines for movie lines. The nearest movie theater to our sailboat was in Oswego, a twenty-five-minute drive on winding roads that curved through apple orchards, fields of corn, dairy farms, and one-street small towns with boarded up restaurants, gas stations, and pharmacies.

Oswego is New York State’s only port on Lake Ontario and a gateway to shipping throughout the Great Lakes. The name derives from the Iroquois language, os-we-go, which mean “pouring out place.” Currently, Oswego exports locally produced soybean and grains to offset shortages as a result of the war between Russia and Ukraine, two of the world’s largest grain exporters.

The State University of New York at Oswego, the Oswego canal, the harbor, and post-industrial decline characterize the town.

We wanted to see Baz Lurhmann’s Elvis (2022) a two-hour, thirty-nine-minute epic mishmash of biopic, musical, melodrama, and opera. At the Cannes Film Festival in May, an unprecedented twelve-minute standing ovation followed its premiere. The glitzy biopic advertising notwithstanding, this color-saturated fable exposes how capitalism destroys people and distorts artistic expression. We figured a Tuesday late afternoon matinee at the Oswego 7 in a small Lake Ontario harbor town would be empty. The Art Deco style Oswego 7 was built in 1940, and opened in 1941 at the start of World War II. In 1988, it was named to the National Register of Historic Places, and in the 1990s, it was converted to a multiplex. By 2022, after its pandemic closure, the theater is now part of the Oswego Downtown Revitalization Initiative. Although eighty years old, the Oswego 7 has been updated for accessibility with closed captioning, assisted listening systems, and audio descriptive headsets.

When we arrived in Oswego, nearly every parking spot was taken within two blocks of the theater. In front of the theater, a few Bird scooters were parked by the large one-sheets for Elvis and Top Gun: Maverick. Inside, young families carrying rolled-up blankets and older adults hauling extra-large popcorn bags packed into the old art nouveau theater, now outfitted multiplex-style with luxury reclining chairs. It was five-dollar Tuesday, and every seat was filled. The words “only in theaters” appeared in every one-sheet and trailer.

And Elvis?

Despite the critiques from the New Yorker and Variety calling for more narrative and character development—vestiges of realist mainstream cinema—Elvis excels and revels in excess, swirling together black music, early rock and roll, poverty, sexuality, and a sad life story of drug abuse and loss. It defiantly, resolutely, and unabashedly bursts open with an anti-realist visual frenzy, a sort of avant-garde blockbuster with a primary color palette. The film’s jagged editing and postmodern pastiche of music and comics refuses to allow the audience to identify.

Austin Butler, the youngish actor playing Elvis with superhero undertones, performs with such mysterious intensity and inaccessible interiority that every other character feels small and flattened, like a comic strip. His twitches and shakes and stares flood over the screen in a world separate from the other characters, a man possessed by rock and roll. The Elvis songs in the film such as “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” “Hound Dog,” “In the Ghetto” and “Tutti Frutti” molt and shake off their rock and roll aura. In its place, operatic arias expressing the inexpressible in theatrical surround sound envelop this tragic story of addiction and capitalism.

West Frankfurt

My mother Alice loved going to the movies all her life, whether in West Frankfurt, Chicago, Houston, Miami, Charlottesville, or Ithaca. She had wanted to act in plays in high school, but her hearing impairment derailed that desire. When she was five, she lost her hearing to scarlet fever. Because interacting with others was hard for her if she could not supplement with lip reading, her theatrical dreams never materialized.

Back in the 1930s, accessibility and equity for those with disabilities did not exist. My mother spent most of her life camouflaging her disability by making sure her reddish blonde hair covered her hearing aids. She often had difficulties in fully understanding conversations, which she disguised by smiling and nodding her head. She never talked to anyone beyond our family about her hearing impairment. Silence engulfed her.

Alice developed an almost religious adoration for the theater and movies. ln her 70s, she became fascinated with opera. She loved the supertitles for the Mozart operas we attended at the Chicago Lyric Opera, wearing the fancy Harvé Bernard black suit she bought for half price at Von Maur’s, getting her hair done, and meticulously applying her make-up and lipstick. I imagined her devotion to all three was designed to mask her hearing loss and separation from the hearing world. Friends and family-by-marriage wonder why a working-class coalminer’s daughter with a severe hearing disability would so love theater, movies, music, and opera, art forms so dependent on deep listening to voyage into nuances and details.

Growing up as the daughter of a hearing-impaired mother, this question never occurred to me. Ever. I am more startled—well, if I am completely honest, offended that anyone would ask this, betraying their assumptions that immersion in the performing arts requires able bodies and full hearing. Although my mother experienced the performing arts differently than any of my questioners, these experiences infused her with an almost spiritual joy. I accompanied her to many performances. I always carried a small notebook and pen in my purse to write down what she could not hear but could read. I knew I would need to explain some plot points and meaning afterwards. I never considered that other people didn’t have to do that. These debriefings bonded us in ritual, a deep connection through translation and interpretation.

When my mother Alice was in high school in the late 1930s, she worked as an usher at the local cinema in West Frankfurt, Illinois, a small town in southern Illinois in the middle of coal mining and Ku Klux Klan country. My grandfather, an immigrant who dropped out of the eighth grade in Sterling, Scotland, worked in the mines and in union organizing to create a safe workplace for the African American, Irish, Scottish, Italian, and German immigrants digging beneath the rolling hills of Southern Illinois, more like the mid-south than the Midwest.

When my mother could no longer walk unaided and stayed in bed in her assisted living facility for most of the day watching CNN and worrying about the Democrats dealing with Trump, stories poured out of her like spring rain. She told me she loved wearing her blue movie usher’s uniform because it included a little hat. She savored the Hollywood crime films, romances, and comedies. She positioned herself in front of the speaker during screenings so it would be louder for her “good ear,” the one with less damage.

I asked her, why movies?

Alice told me that when you went to the movies, people were huge—and so were their lips, which made lip reading easier. She could grasp some of the words, but not all. An added plus: no one spoke to you from the side or from behind you or in groups, ways of interacting that barricaded her from engaging language and people. The actors on the screen spoke directly at you, amplified with speakers.

Always a devoted Scots-Irish Catholic, my mother believed that when God took something away from you, like your hearing, He gave you something else if you could find it. She believed she possessed the sixth sense, an ability to intuit people and stories beyond what was exposed.

She maintained it was a blessing, a special gift that let you move more deeply in a different world. She detected the sixth sense had skipped my brother Byron, an oil executive, and me, perhaps pounded to dust by advanced degrees and jobs. But she was relieved that my niece Danielle and my son Sean showed signs of possessing it although they had not yet found it. She insisted that movies and opera were designed for people with that sixth sense who could see and understand more than people without hearing impairments.

In late 2009, when she refused to eat and saw demons crawling on her gold linen bedroom curtains, she ended up in the psychiatric ward in Hinsdale Hospital in a Chicago suburb. During the one hour a day allotted for visitors at 6 p.m., she whispered to me that she despised the psych ward. She complained she didn’t have enough ironed clothes and felt embarrassed that she looked sloppy for the nurses and psychiatrists who were gentle and kind to her. She grumbled the ward lacked television and movies, a silent prison of white walls and glaring fluorescent lights.

My mother encountered problems following conversations in large groups of people at parties and even at farmers markets. The excessive ambient noise she could not process triggered severe anxiety that prompted her to look around agitatedly or pick at the skin on the top of her hands. She either fell silent or talked nonstop in order to not have to struggle to interact. In a small group with everyone sitting at a table and talking one at a time, she transformed into an extremely social being, like a blue iris opening up to the sun in May. In theaters she could live in a world where all the words came through and entered her. In theaters, she was liberated from the worries and traumas of peripheral noise or people mumbling behind her like beavers chewing on a log.

Iowa City

The first out gay man I ever met was Charlie, a spirited graduate student in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop who adopted a few of us in the undergrad poetry workshop. He grew up somewhere in the South and ended up in Iowa City to attend the University of Iowa. A cinephile who relished the feeling of the screen engulfing him like a tidal wave in the Pacific Ocean, he was an unapologetic movie addict. He dragged Kimiko, Ann, and me to see The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) in a downtown theater in Iowa City. We were sophomores then. He jibed we needed a break from subtitled French and German art films at the Bijou Cinema on campus. It was my first cult film, and my first experience of a mostly queer audience.

Charlie knew all the words to songs such as “Science Fiction,” “Time Warp,” “Sweet Transvestite,” “Damn It Janet” and sang along, losing himself in the performative film. He also seemed to know everyone else in the theater, gay men seeing the film for the third and fourth and fifth time. He loved lead actor Tim Curry, dressed in drag with a black leather corset, black lace panties, and black hose held up by garters. Charlie chided us to stop being suburban girls reading Jane Austen and William Blake in English Department courses.

The drinking age in Iowa was 18, and the next day, Charlie hauled us to a new bar on the outskirts of Iowa City. Kimiko, Ann, and I frequented bars like The Mill, where discussion about poetry and politics blended with live blue grass music in the background. The new bar occupied a converted empty store front. Drag queens dressed in shimmering pink and purple gowns lip synched to Aretha Franklin and Dionne Warwick. After bringing us to The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Charly prescribed a real drag show, in person. He admonished us that gay men were everywhere, not just in movie theaters.

Westchester

At my Catholic all-girls high school in the Chicago suburbs, hardly any of us dated. It just never occurred to us. Perhaps the nuns had sucked out all of our sexuality, transposing it to physics, art history, volleyball, and group prayers. The boys studied at St Joseph’s High School and Fenwick, all-male private Catholic schools that pushed Charles Dickens, hockey, basketball, and the fear of Jesuit priests who forced rebels and the disobedient to scrub the floors with a toothbrush. The girls from Proviso West, the nearby public school, told us they went to the movies to hold hands in the dark and sneak wet tongue kisses with their boyfriends. They ignored the films. But for us, the movie theater offered sanctuary away from our families, from the nuns, from endless policing of the length of our blue plaid uniform skirts which we transformed into mini-skirts by rolling them up from the waist as soon as we were out of sight of the nuns.

We rode the bus to the Hillside Movie Theater near a run-down 1950s shopping mall to see Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968). Before the film, an organist played 1940s swing songs over slides advertising realtors, muffler repair shops, tombstone carvers, and Sears Roebuck. The film sweated off the screen, pulsing with teenage desire, steamy and sexy with Olivia Hussey’s heaving decolletage, Leonard Whiting’s flowing hair, and endless longing gazes. There were a few other pods of teenage girls spread around the empty theater. We must have seen the film a few years after it came out as a second run.

In 1972, in the fall of my senior year of high school at Immaculate Heart of Mary, a group of us skipped school to drive to downtown Chicago in our friend Joan’s older brother’s Impala. We went to see A Clockwork Orange (1972), a violent, dystopian, male-driven film featuring angry teenagers, based on the Anthony Burgess novel and directed by Stanley Kubrick, at a massive State Street theater. We wanted to see the film because it had an X rating. We knew it would never come to the suburbs. We clustered in the empty balcony. We thought we would be less noticeable there, because all the regular patrons—mostly older men—were spread across the main floor. The film had almost no women in it. The violence repelled us so we closed our eyes. The thrill was not the film but playing hooky for our very first time to see an X-rated film that did everything the nuns said we could not. In the theater, we could be bad girls for two hours.

Ithaca

Elvis is also playing theatrically in Ithaca, New York where I live, simultaneously at Regal Cinemas, the corporate multiplex at the mall, and Cinemapolis, the local nonprofit independent art cinema downtown.

The legacy film distribution strategy of run-zone clearance, a holdover from the studio era eighty years ago where films rolled out from exclusive first run to second run, has been gutted. Now, teenagers and blockbusters occupy the multiplexes like a conquering army from another galaxy. The older gray-haired crowd, as The Hollywood Reporter describes them, who want films without violence and with characters, dialogue, and artistic complexity, who like international and indie films, occasionally go to the art cinema. These two different exhibition worlds no longer compete. Every theater hunts for bodies.

Cinemapolis is the only art house showing international and independent movies within a 100-mile radius in our part of central New York. And for those in wheelchairs like my mother, the theater’s wide halls and plenty of accessible options from bathrooms to dedicated spots in the theater for the mobility impaired make movie-going about what you see on the screen rather than worries about how to navigate a space. Independent exhibition is a world beyond the theatrical wars of the media transnationals and the tech companies. Art cinemas have lived in the world of day-and-date release for at least a decade. Their vision of theatrical exhibition is community-located and mission-driven rather than the saturation release of the blockbusters to thousands of theaters at the same time. Our local cinema rents out space for a church, retirement parties, kids’ birthdays, and business meetings. Community groups run specialized screenings on topics spanning the Adirondacks to bicycles to Pride month. Independent filmmakers roadshow their films, driving them from theater to theater for one-off screenings and discussions. In the art house sector, “only in theaters” means a gathering place for communities and for art and ideas exiled from streaming services and multiplexes.

Houston

In mid Fall of 2009 when the humidity had finally shrunk down like a cashmere sweater in a dryer, my mother and I attended the Houston Cinema Arts Festival. She had flown down from Chicago. At my brother’s home in Katy, a Houston suburb without trees and consisting of sprawling newly constructed McMansions for oil industry executives and medical center doctors, she opened her suitcase in the guest bedroom on the first floor and sobbed. She had not packed many clothes in her large green suitcase and what was there—a black suit, a pair of black low-heeled dress shoes, a yellow sweatshirt, a pair of jeans, and a red plaid flannel nightgown– did not go together.

I told her I had packed some blouses that would fit her, and we could go to Macy’s to shop for some dressy pants and a new blouse or two. She looked frantically for her peach lipstick in every zipper of the suitcase, and then repeated it over and over again. I had to close the suitcase and remove it from the room. Three months later, after her stint in Hinsdale Hospital, my brother Byron and I moved her down to the Houston suburbs so she could be in a residential community with others and have family closer.

We stayed in a massive Hyatt Regency in downtown Houston with a soaring twenty-nine story atrium where Logan’s Run (1976) had been shot. Because I worried parking would be too far away for us to manage, we took cabs to the theaters. She said that door-to-door transportation made her feel like a VIP. She was not walking well by then, but she sported a purple and blue speckled cane. She was delighted that the ushers at the Houston Museum of Fine Art theater let her enter before the rest of the audience and sit on the top row so she could avoid the stairs. She thought they offered that special treatment because they were Texans and had more manners than Chicagoans. She did not know about the Americans with Disability Act that ensured accessibility for her. We watched Tecknolust, (2002), Lynn Hershman Leeson’s feminist sci-fi parable featuring Tilda Swinton. Richard Herskowitz, the brilliant, gutsy programmer of the festival and one of my closest friends from graduate school at the University of Wisconsin, had asked me to conduct a post-screening discussion with Lynn and Tilda for a DVD extra.

I was thrilled but anxiety rattled through me. I was a fan of both women, a bit gobsmacked by them as brilliant goddesses of the feminist avant-garde. I worried this experimental narrative about clones would be too hard for my mother to follow. She told me not to worry, all she cared about was watching me on the stage in the white linen blouse she had bought for me a few years earlier at Marshall Fields. She had painstakingly ironed it in the hotel room that morning, flicking water from a paper cup on the fabric to ensure the points on the collar steamed flat.

Like opera, she discovered film festivals late in life, after my father died from a massive stroke that blew out his brain functions and ability to speak or move in 1999.

Over the years, Alice was my plus-one to the Virginia Film Festival, The Miami International Film Festival, the Chicago Irish Film Festival, and the Houston Cinema Arts Film Festival. It surprised me she liked festivals so much. At first, I thought it was just a way to hang out with me and not be lonely. When I probed, she said, yes, she liked being with me and being in a group of people doing something together. She also liked that most of the films from other countries had subtitles, and as a result, she could understand them. She told me for her it was like going to a Catholic Church without communion or a priest, where she could just sit, be quiet and calm, and watch the screen, an altar of art only in theaters.

Everywhere

The divide between only-in-theaters and streaming is not clear cut. In April, the Los Angeles Times reported that streaming had its worst week ever. Netflix lost subscribers and laid off staff. Theatrical box office for 2022 is expected to be double that of 2021, yet streaming services have multiplied. However, simultaneously the theatrical movie business is shrinking into a few blockbusters and genres such as comic-book action films, horror, and family films. The Oswego theater where I watched Elvis ran only blockbusters. These news stories about the reorganization of distribution and exhibition in the film industry ignore how cinemas have been outposts promoting ways of thinking not found in mass culture consumption.

The very first time I experienced a deconstruction of the hidden political ideologies of a popular culture film was at a 10 p.m. screening at the Bijou cinema at the University of Iowa. I was a first-year English major overwhelmed that I was being pushed to analyze deep hidden meanings and complex structures in novels rather than to just be swept away by them. The film was The Wizard of Oz (1939) which I had seen many times on television as a child. Before the screening, some friends smoked a joint outside near the Iowa River, but I did not, as I wanted to stay awake for the film after studying for hours in the university library.

When I walked in, I was given a green handout with an incendiary political and visual analysis of The Wizard of Oz. Some very intense graduate cinema students obsessed with ideology delivered a short pre-screen lecture, commanding that we “read” the film against its upbeat musical genre grain to see it as a politically conservative anthem to resurgent capitalism. The manifesto-like handout rippled with feisty language, contending that the film unfolded as an allegory for America coming out of the Great Depression and a propaganda anthem inculcating capitalism. The Yellow brick road symbolized the quest for success and riches. The Emerald City was a metaphor for money. Dorothy, the Tin Man, the Lion, and the Scarecrow were workers united in solidarity and marching, then bought off at the end by individualism and consumer capitalism that filled imagined absences.

I remember thinking about my mother as I watched the film that night, because like the characters in the film, my mother was also missing something—her hearing. I had never considered that these four characters with their various disabilities and losses were united in solidarity. Years later, Salman Rushdie, in one of the most astute analyses of The Wizard of Oz, offered a quite different counter-reading: that the film exposed a radical celebration of postcolonial hybridity and interspecies solidarity. He argued who would want to stay in Kansas, a dump in black and white? He contended the film celebrates a liberatory story of escape from family and tradition.

It was the first time I ever attended a film where a pre-film talk asked me to read against the grain and against my own cinematic experiences. I wondered how anyone learned how to do this kind of radical interpretation gutting a children’s film now transformed into a college circuit cult film to watch while stoned. Ideas and debates electrified the small theater in the student union. This was that kind of only-in-theaters experience where deconstructions of buried ideologies opened an entirely new world to me. I felt completely intimidated, poured into a world of ideas about which I knew nothing. I left with new eyes.

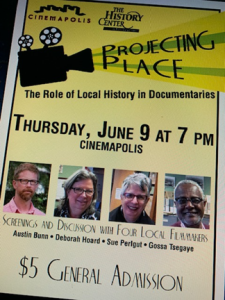

The last screening my mother attended was at Cinemapolis in Ithaca in 2016. My colleague Gossa Tsegaye, an Ethiopian-born community media maker with fifty years of experience, had teamed up with the History Center to screen a selection of his documentary shorts such as Smile in the Wind, Dream Street on Buffalo Hill, The Jungle’s Edge about different neighborhoods in Ithaca. The evening was entitled “Projecting Place: The Role of Local History in Documentaries.” My mother dressed up in her black denim jacket with little rhinestones on the collar, carefully applied her peach lipstick, and asked me to bring one her favorite gold necklaces that my father had given her as a birthday gift.

Because I needed a wheelchair to transport her, I made sure I left her assisted living facility ninety minutes before. She was calmest when we went slowly, as though walking underwater. Each part took time and for me, a Zen-like sense of being in the present not for spiritual solace but so she would not fall: getting into my blue Volvo station wagon, folding the wheelchair, finding handicapped parking, putting up her handicapped parking medallion, pushing her in her wheelchair into the theater, finding the spaces set aside for wheelchair-users, going to the bathroom, getting popcorn, and writing on a notepad to explain to her what was going on.

She was excited about going to the movies, especially since it was all on one floor, wheelchair accessible, and without noisy large crowds that would have interfered with her ability to hear—and to think. Cinemapolis’ Executive director, Brett Bossard, greeted her with a smile and shook her hand. Once we settled in the wheelchair-accessible spot in Theater 5, Gossa approached her. He bowed, and told her he was honored to meet Mrs. Zimmermann and thanked her for coming. She whispered in my ear “It is something else to meet a famous film director in person. Only in Ithaca!” After the screening, we split a hamburger and sweet potato fries at Red’s on Aurora Street, one of the wheelchair accessible restaurants in town that did not play loud music. She had difficulty hearing words when loud background music blared. The combination disoriented her. Gulping down the freshly squeezed lemonade, she leaned in from her wheelchair and confided to me that my colleague Gossa made films about an Ithaca she did not know existed, someplace else beyond the town’s usual story of lake and ethnic restaurants and health food. And then she told me that after moving from Chicago to Houston to Ithaca, the screening felt like home.

# # # # #

Patricia R. Zimmermann is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Screen Studies and Director of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival at Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York. The author or editor of ten books, her most recent are Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics (Indiana 2019) and Flash Flaherty: Tales from a Film Seminar, (Indiana, 2021).