On June 19, we published photographs from Memory Trace, which is part of Fazal Sheikh’s magnificent Erasure Trilogy about the attempted erasure of Palestinian history and life after the Nakba. We said we would publish reflections about photographs from Erasure that were first shared at Storefront for Art and Architecture in 2016, where Fazal’s photographs were on display at Storefront’s gallery space. At this inspiring gathering, scholars and artists, Emmet Gowin, Amira Hass, Rashid Khalidi, Rosalind Morris, Shela Sheikh, Michael Wood and Sadia Abbas were each asked to speak about an image from the trilogy. Some spoke extemporaneously and some—like Rosalind, Shela, and Sadia — read from texts we had written. Rosalind chose an image from Desert Bloom and Shela from Independence/Nakba. We reached out to Rosalind and Shela to ask them if they would share their wonderful meditations with our readers, and they generously agreed. On June 25, we published Rosalind Morris’s reflection. Today we publish Shela Sheikh’s meditation:

Independence/Nakba

Reading Images: On Memory and Place

Shela Sheikh

“Reading images.” And yet, each of us was asked to read an image. An impossible task. For does one not always begin to read—and hence to respond—from elsewhere, in citation?

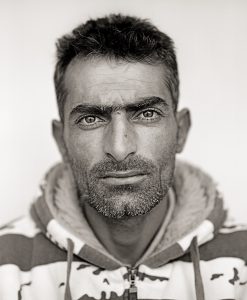

Stepping momentarily outside the frame in order to offer some context, and as such immediately betraying the singular… the image in question is from the series, Independence/Nakba, which both closes and in many ways retroactively inflects the entirety of Sheikh’s Erasure Trilogy. Here, 65 diptychs juxtapose portraits of persons from both “sides,” so to speak, of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, with one pair for each year between 1948—the year in which the State of Israel was established—and 2013, each pair increasing in age. As is the case across the trilogy, the event of 1948 looms heavily, its fissure still palpable. Or, more specifically, the 15th of May: officially celebrated annually as Independence Day, and simultaneously mourned and commemorated, unlawfully, unofficially, as a day of catastrophe (Nakba). And it is precisely within the battle over the meaning and memory of this event that this series quietly, yet forcefully, takes its place.

But here I’m contextualising, rather than reading. Or, as is always the risk, interpolating.

So, returning to the image… Two subjects address us. Two parallel gazes, directed not upon each other, but upon us, burdening us with the labour of looking and all its discomforts. Whilst in the context of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict a search for “recognition” is undoubtedly at stake, there is no room for mere spectatorship here, no watching from afar as two or more communities seek means for co-existence—or, perhaps better, co-resistance. Co-resistance, among other things, to the hegemony of on the one hand memory and on the other forgetfulness, or imposed amnesia. Rather, it is us, the viewer, who is forced to enter the scene. Can we ever respond to one without betraying the other? Can these gazes touch us without our reciprocal, active touch? Where to place ourselves, here, where, in order to view “the image,” one cannot turn one’s back on one, take “sides”? Here where, in order to view one, one must nonetheless remain partial to the other? But in this fraught context, can one ever remain impartial, objective?

Two subjects, mid-way through the continuum. Young enough not to have seen the events of ’48 with their own eyes, yet old enough to have witnessed just once removed; to carry the stories of their parents and grandparents, to know the significance of ’48 and its material repercussion. Two subjects, it turns out, of almost my own age. Narcissism creeps in, inevitably. But is this not always the case when faced with a portrait: the search if not for empathy then at least some form of connection or identification? Given that there’s one pair for pretty much each of our ages, few of us are excused. What, then, is our permission—or rather, our obligation—if not to narrate, then certainly to engage? How must we, each in our own way, in our own context, respond to the politics of nation-building and myth-making? How to orient ourselves within the minimal yet enormous chasm that lies between the two parts of the image—an element of the image that, I would propose, harbours as much as the “portraits” proper? This gulf that is at once a barrier—geographical, material, religious, ideological; the list goes on—and a thread of alliance: the lasting bonds that precede the act of division of ’48, for instance.

So, an image. Or, I would venture to propose that this image is in fact but one of 65 double elements that together make up a single image. A single portrait of a generalised condition of both hyper-memorialisation and hyper-amnesia that, unless acknowledged and responded to, risks closing down the future. If, as we well know, a photograph is always a punctual moment in space-time, a future anterior work of mourning, then this series-slash-image, somewhat arbitrarily closed, bears witness exemplarily to the passage of time, to the movement of discrete moments within history, to their potential capture and instrumentalization.

But if we’re speaking of history, where are the archives, the witnesses? Unlike in the previous volumes, no information is proffered. Nameless, mute and opaque, perhaps what these subjects bear witness to is the impossibility of human testimony, the limits of language. An impossibility and frailty that is responded to in the previous volumes through an almost over-abundance of “information,” pictorial and linguistic, precarious as this always remains. Through the ruins, landscapes and faces that—each time as “portraits”—are in some way ventriloquized, clamouring towards both the poetic and the evidentiary. Here, however, if there is erasure, it is predominantly psychic and collective, and remains invisible. Erasure as a ban on mourning, commemoration, even “resolution.” But, a question to conclude with… insofar as psychic traces, unlike the material, resist not only interpretation but also, perhaps, erasure, might we find here an avenue for resistance to the double erasure—the “erasure of erasure”—borne witness to by the previous works?

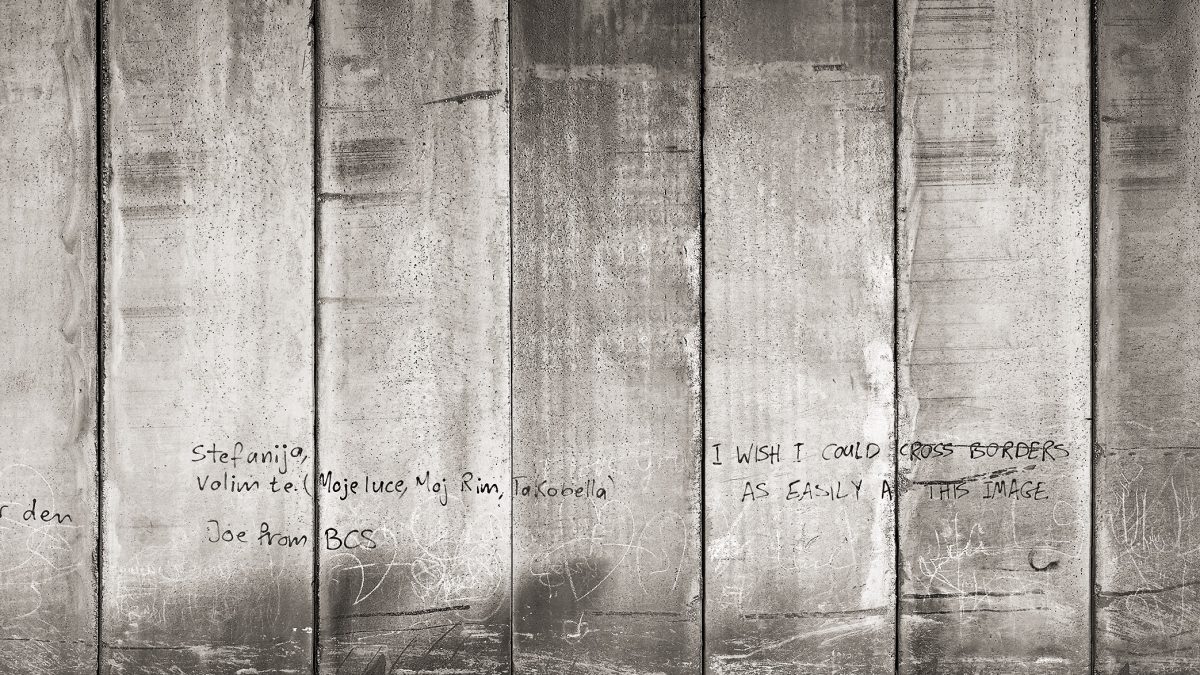

31°50‚41”N / 35°13‚47”E

Israeli side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of Neve Yaakov and Beit Ḥanīna. Just beyond the wall lies the neighborhood of al-Ram, now severed from East Jerusalem.

Images: Fazal Sheikh, Independence/Nakba, part of The Erasure Trilogy (Göttingen: Steidl, 2015)

Shela Sheikh is Lecturer in the Department of Media, Communications and Cultural Studies at Goldsmiths, University of London, where she convenes the MA Postcolonial Culture and Global Policy and the PhD Cultural Studies. Prior to this she was Research Fellow and Publications Coordinator on the ERC-funded Forensic Architecture project (also Goldsmiths). A recent multi-platform research project around colonialism, botany and the politics of the planting includes ‘The Wretched Earth: Botanical Conflicts and Artistic Interventions’, a special issue of Third Text co-edited with Ros Gray (vol. 32, issue 2–3, 2018), and Theatrum Botanicum (Sternberg Press, 2018), co-edited with Uriel Orlow, as well as numerous workshops on the topic with artists, filmmakers and environmentalists. Her current research interrogates various forms of witnessing and testimony between the human, technological and environmental. Together with Wood Roberdeau, she co-chairs the Goldsmiths Critical Ecologies Research Stream (https://criticalecologies.gold.ac.uk).