This is the second part of Patricia Zimmermann’s meditation on COVID-19. Part one can be accessed here.

COVID 19 Movement III: Presto

According to our librarians at Ithaca College, only the most recent books on documentary history and analysis could be found as e-books,

The theoretical books in critical ethnography, critical historiography, and theory were limited to hard copy.

Our librarians ordered every e-book on documentary they could find, squeezing out budget from small cracks so students in my History and Theory of Documentary class could have some readings. Plenty of books on new media theory had been published as e-books, so that covered part of my class, but not the abstract part, the meta.

Then, the college shut down.

The administrators told the faculty that we had one week to “migrate” our courses to “remote instruction.”

COVID meant shelter-in-place. No more F2F (face-to-face) classes as they have come to be called in social media faculty forums. F2F has become a phantom, a phantasmatic, a fantasy in this COVID world of invisible viruses, illness, death, and screens. We migrated from the embodied sensorium of the classroom to the ephemerality of screens. From three dimensions to two. From a world of chiaroscuro to flat.

This massive migration of college classes to the digital came with a great work speed-up.

Many colleges, including my own, insisted on propagating ideas about “student-centered education,” a neoliberal construct of consumerism and comfort displacing the discomfort of ideas, debate, academic disciplines, and intellectual rigor. A dangerous shift from the collective to the individual, from abstract thought to feelings.

To be student-centered, we were told that it was important to teach in what is called a synchronous mode, in real time, rather than in asynchronous mode, where students did the work on their own time. We were encouraged to stay in touch with our students, send emails, be available on Zoom for open office hours, and understand students’ anxieties and trauma during the lockdown.

These repeated incantations ignored what faculty actually had to do: redesign, restructure, and reconceptualize courses on a new interface, in a new format, and under nearly impossible conditions with students who were so consumed by fear of death and disease and isolation in their high school bedrooms they could not focus. And all of us, whether at elite schools, public universities, or four-year private colleges had to do it fast.

Presto, I thought. Very fast. Tumultuous. A forward driving rhythm with contrapuntal tension. Presto.

I scrambled to cut films and new media projects out of my syllabus, not to make the course easier, but to respect the labor of our librarian who digitized titles for Sakai, the college’s learning system. He was swamped by requests rushing in from across campus. He was digitizing ten hours-plus a day to get it all done.

When the Governor instituted the PAUSE which shut down everything, this librarian brought in backpacks and shopping bags to pack up all the DVD titles faculty needed, with a bunch of external drives. He would have to digitize from home.

I cut and pruned and honed, trimming down titles as much as I could. I convinced myself that instead of my carefully curated sequencing of films and new media to jolt students into novel ideas through shock or through pleasure, I needed a new plan. This dialectical curatorial approach would not work online.

So I brainwashed myself into thinking this could now be a “slow read,” a deep dive into close readings of the texts. In fact, Tim Murray, my close friend and comrade who teaches at nearby Cornell University, offered the argument that all undergraduates need to learn to read films and new media carefully on the formal level of close textual analysis, so this was in fact not defeat, but a good thing, a cleansing in a way, a paring down to what matters and developing transferable analytical skills.

During this scramble to transition my courses to online, I tackled Mozart’s Sonata in A Minor. Written in 1778, it commemorated his mother’s death with a mix of pounding repetitive chords and flying lines of fast notes, then a gorgeous sweet andante movement, and finally the third movement, presto. It is tumultuous, with surging dynamics and juxtapositions of soft and loud, sweetness and rage. The Sonata in A Minor is just one of two Mozart sonatas in a minor key.

I realized this so-called mass migration to remote learning was not a simple change in the mode of delivery, but a substantive reconceptualization that catapulted me and other colleagues into presto. Not the presto of magic shows, but another presto, more like a runaway train—fast, furious, contrapuntal.

But, as critical historiographers say, there is the straight story and then there is the crooked story.

The straight story seemed to emanate from administrators emphasizing student access to media technologies, teaching synchronously as a matter of simply transposing what we do in classrooms in a large media school to an online environment. It meant an uncritical technofetishism of workshops, tutorials, and webinars on various gadgets and interfaces that disguised and repressed the intensifying anxieties, overwhelming work speed-ups, and daunting conceptual labor.

The idea was to keep it all the same, as though nothing had happened and as though the Zoom screen did not flatten our affect and transform our images into postage stamps.

The straight story meant asserting without critique that students needed high-end gear to make their films and videos, and that the college needed to get it to them at all costs. One of the engineers in the Park School called me, worried about how to decontaminate cameras with all their recessed surfaces. He had called various equipment places in New York where contacts of his worked.

Nobody knew how to decontaminate lighting gear, sound recording equipment, or cameras. Our engineers worried if they entered the building to get gear to ship to students for their thesis projects, they would die. Or their children would die. Or they would be sick for weeks. They worried that if they refused to take the risk so that the college could pretend everything was the same (the straight story), they would be fired.

Their crooked stories unsettled me.

And as crooked stories do their work, their bends and forks and branches push us to see differently, to realize that the straight story of official histories and institutional statements is disingenuous and camouflages the terror of change. Historians like me look for turning points and shifts where movements and layers recalibrate and reform in the crooked stories where the tempo is not andante, but presto, where contrapuntal voices complicate the melodic line.

A younger colleague called me crying.

It was impossible to do all this synchronous teaching with a two-year-old and a partner who also worked at home. Newly tenured, she wanted to know who I thought would be fired. The college, a small school without a big endowment that depends on tuition to operate, continues to worry about shrinking enrollment. Workforce reductions were mentioned at every webinar conducted by what is called the Senior Leadership Team. This specter loomed over even tenured faculty, since financial exigency takes away normal protections.

My colleague said it was impossible to even think. She could not write. She could barely read. Now she had to figure out how to manage cooking dinner, shopping safely, caregiving, finding a quiet place to do her Zoom meetings with students, grading, and answering more and more emails from students who could not meet any of their deadlines.

I joined forces with some other senior faculty advocating for extensions to tenure clocks, the adoption of Pass/Fail, and the abandonment of student statements. We were not alone. It was a grassroots national movement.

Another woman colleague wrote me a long email. She said she could not think as fear infused her brain and her heart. Anxiety consumed her like an avalanche.

She has a one-year-old, no childcare, a geologist husband who works in another state, and continuing pressure to be available to students and keep her courses to a synchronous schedule. Meanwhile, she is doing all the shopping, the cooking, the cleaning, and the childcare while also tracking down students who never attended class or responded to emails.

On top of that, she told me the college keeps messaging her that it is having financial problems and needs to downsize. She asked me this: will I be fired? She had heard that most of the part-time and one-year contract faculty were not being renewed, and that class sizes would be increased.

She said, “I feel terrorized, and the speed of all of this, of just one day, leaves me depleted.”

I told her we needed to do a Zoom some time, just so she would not feel so isolated.

In that Zoom meeting, she told me that she did not think that anyone understood her research (she is a massively productive feminist social scientist in communications). She did not feel any support from her department. For her, this migration into remote learning meant a migration into a work speed-up that ignored the added pressure of working at home without help or childcare. Her isolation offered no community. My heart broke for her.

Another colleague worried that the program he directed would be cut because of the budget crisis and the perils of a significant drop in the first-year enrollment for the fall. He said that nobody has spoken to him directly, and as a result, he has morphed into a Kremlinologist, watching the administrators’ webinars for the smallest clues, but discovering only more anxiety and fear. Workforce reductions. No international travel. No raises. Larger class sizes. Prepare each class for fall three ways: as face-to-face, remote learning, and hybrid. Work speed-up. Presto.

If my emails were transcribed into musical notes in a score, they would reveal the last movement of a sonata, presto, with multiple voices layered in counterpoint.

One student told me that he could not turn in his paper on time as his father, an emergency room doctor, had contracted COVID in a Philadelphia hospital. A young woman complained that she could no longer work to her strengths—she didn’t do well in theory courses, this was the fourth one since she dropped all the others, she preferred hands on, doing things, not reading or writing. She said that the order to shelter in place robbed her of making videos, and therefore she could not do my theory course because without the balance of practical work which she much preferred, it simply did not matter.

In contrast, another student wrote and said going online offered something he did not have before: discussion postings where he could think about the documentaries before the discussion and get feedback. Another said moving online and sheltering in place offered solace and respite from the pandemic. With no parties, no socializing, no clubs, no internships, no extracurriculars, and no love life, she had time to focus on her readings.

Then there were messages from colleagues, forwarding articles about the collapse of higher education, the digital migration perhaps becoming the great annihilation, where only elite well-endowed universities would remain, and where institutions like mine would have to reconfigure into something unrecognizable or evaporate completely.

The fast-paced presto of the Honors Program Rapid Response Salons on COVID-19 that we produce weekly as an interdisciplinary faculty group has become an exciting space that renews us with community and purpose. Even some administrators have joined the salons, eager to swim in the presto of evolving ideas. A retired much-admired colleague wrote me after participating in one of the Friday salons. She said “ideas will get us through this.”

The third movement of the Sonata in A Minor pulses with tumultuous cascading motifs in presto with many voices.

When I play it, I think of the possibility of my own mother’s death from COVID, of the death of higher education as we all once knew it or perhaps, more accurately, dreamed of it, of the death of calm and solace, the death of being with others and forming communities.

We are all in mourning for losses we cannot yet name.

We are all in presto, speedy notes tumbling out in all keys, some of which we do not recognize and cannot yet play with texture, nuance, dynamics, or style. Presto.

COVID-19 MOVEMENT IV: Rondo

The drone flew over Buffalo, New York, the second hot spot for COVID in the state. Empty streets. Buildings. Lake Erie. A lone jogger ambled slowly down a sidewalk in the city center.

The exhilaration of virtually flying over and outside contrasted with my daily life now compressed into Zoom and FaceTime.

Still from “Drone Footage of Buffalo, NY in Coronavirus Lockdown,” Dan Oshier Video Productions, April 8, 2020. https://youtu.be/C-_fB7eaBOE.

The first was comprised of aerial long shots. The second was a flat, immobilized world of close-ups, interior spaces, bad lighting, white walls, bookshelves, and couches.

While COVID snakes through our lives and spaces invisibly with no form or pattern, the visual regimes of the pandemic split into two directions: the aerial shots of drones offering a first person point of view as the virus empties cities, and then, the small, intimate, close-ups of Zooms, FaceTime, and Webex in teaching, in meetings, with friends, on the multitude of webinars proliferating in digital space or even on CNN or MSNBC like daffodils in April.

Critical theorists argue that binary oppositions are unfashionable, retro, reductionist. They form the spine of fairy tales and commercial narrative media, fictions which simplify the layered entanglements of the world and our psyches, which unfurl in more complex polyphonies and webs.

But these new visual regimes of the long aerial shots of drones and the close ups of Zoom and other interfaces demand other ways of thinking, beyond the binary or even the dialectical.

The drones move, the Zooms are static.

The drones are aerial, the Zooms are ground-level. The drones are of buildings, the Zooms of humans. The drones are high, and the Zooms are low. The drones maneuver, and the Zooms are stationary. The drones are distant, and the Zooms are nearby. It is the difference between the wide-angle, and the extreme close-up.

In short, we now live in a world without medium shots. The artificial intensity of the extreme close-up and the remove of the wide-angle are both ways that living in the pandemic has denatured our lives. The drone takes you outside, but you can’t feel the breeze or smell the flowers; Zoom and FaceTime bring you within inches of each other, but you still can’t touch or be touched. In other words, no matter where the media take us, we’re never really there.

In sonatas, the Rondo stands as a movement, usually at the end of a piece, where oppositions are not binary but constitute part of a structure of alternations between refrains and episodes, multiple recurrences in a tonic key. The refrain repeats, then episodes contrast.

Beethoven’s Sonata in C Minor, also known at the “Pathetique Sonata” concludes with one of my favorite rondos. It is a piece I have picked away at for ten years, the opening movement in Grave, a slow, slow tempo, not spirited but filled with bold dissonant chords, syncopations, rests, long downward cascading cadenzas, sharps, and flats.

The rondo takes the contrasts in the previous movements and releases them in the last. Refrain and episodes. In Italian, “rondo” means round. Instead of opposition, it is a rounding together of the refrain and episodes.

Rondo might be a way to think about the drones and the Zooms, how they mediate our psychic landscapes between fantasies of flying in release above and the physical body realities of being chained to our desk chairs, and computers in the close-up universe of Zoom where the images look like a sheet of postage stamps.

Edmund Cardoni, the curator at the legendary Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center in Buffalo, New York, posted the drone footage on Facebook. Since the lockdown, Facebook and social media usage has exploded, a 33% spike in traffic on some days. While it can be a blessing during the pandemic, as Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias argue in their new book The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism (2019), social media camouflages the neocolonization of digital capitalism where datafying our feelings and affect is the gasoline of global capital.

With all the news in our state focused on the ongoing, heartbreaking, catastrophes of infection and death in New York City, the drone footage popped out as an assertion that there is life outside the city—that upstate exists.

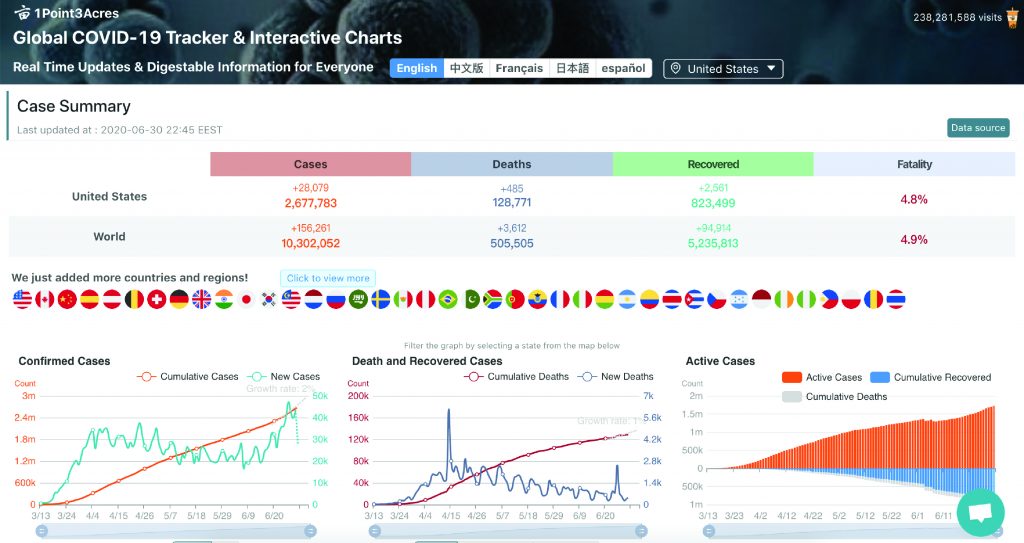

Minutes before I saw the footage, I had scanned a data visualization of the rates of COVID infection across our very large state, looking for Tompkins County, where I live. Our county has one of the lowest rates of infection and only two deaths, both from downstate patients transferred up here for hospital beds and care. But these numbers deceive: our county is mostly white, affluent, and working, with Cornell University and Ithaca College the largest employers.

Still from “Drone Footage Shows Wuhan Under Lockdown,” New York Times, February 4, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/video/world/asia/100000006960506/wuhan-coronavirus-drone.html.

Drone footage abounds in the COVID 19 crisis, posted and reposted on social media, circulated among friends via email. Chicago. Delhi. Dubai. Hong Kong. London. Los Angeles. Mexico City. Milan. Mumbai. Nashville. New York. Riyadh. Rome. San Francisco. Singapore.

It occurred to me that recent drone footage produced by amateur drone pilots, by kids trapped at home with their parents, and by the BBC, New York Times, VICE, Channel News Asia, and Al Jazeera constituted a new genre: COVID Drones. Perhaps one of the most circulated of the drone elegies for a city is the piece on Wuhan now living on the New York Times site. It is also one of the first.

When I reposted Edmund’s Buffalo drone footage, I wrote that drone footage seems to be an emerging COVID genre.

Caren Kaplan, the incredible scholar of drones, replied that drones seem to be the correlative of social distancing, the distancing of drones multiplying the geographies of social distancing. Then B. Ruby Rich, editor of Film Quarterly (I am on the editorial board, full disclosure!) suggested Caren and I do a conversation on COVID drones for Film Quarterly’s Quorum, which runs online. Girish Shambu, editor of Quorum, jumped on enthusiastically. They all suggested that the discussion include many links, a sort of COVID drone playlist. A rondo of refrains and episodes that built into something new.

We said yes—we have known each other for a long time but have never collaborated. We talked on FaceTime, catching up on our baking and cooking strategies, how to find yeast and flour, the pleasures of Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs), how the pandemic brought some new joys, like cooking, reconnecting, shopping local, and working on this conversation.

Our discussion assumed the rondo structure of refrains and episodes on the drones. We noticed an explosion of drone footage during the pandemic from every part of the globe. We put our thoughts in writing, employing the rondo form of refrains and episodes.

It now lives online. I share not as ego; I am not looking to be part of the COVID culture industries that seem like neoliberalism cloaked in critique and theory. Instead, I share as a rondo for you, to see if you want to add a refrain or an episode as in music theory.

1Point3Acres’ “Global COVID Tracker & Interactive Charts,” part of the 2020 FLEFF program Infiltrations: A Different Media Environment, https://coronavirus.1point3acres.com/.

A rondo of collaborative feminist work across Word and FaceTime documents that with renewed hope, ideas that are shared and circulate might just get us through this.

A rondo of two bread-baking, CSA-picking up scholars trying to build a small structure of ideas to say no to chaos and destabilizations everywhere. Here is our piece, “Coronavirus Drone Genres: Spectacles of Distance and Melancholia.”

Rondo: multiple recurrences, contrasting episodes, tonic key.

COVID-19 Movement V: Grave

I wrote this on April 30 of 2020. The same day in 1975 marked the end of the war in Vietnam, or as the Vietnamese called it, the American War.

45 years later, as I wrote this, over 60,000 Americans had died from COVID, more than the 58,000 who died in Vietnam. Less than a week later, the number increased to more than 70,000. The death toll around the globe is nearing 250,000, and over 20,000 are dead in New York City, a global epicenter of the pandemic. I live in upstate New York, a different epicenter, not of death and pandemic, but rather a robust media and digital arts community, many of whom post frequently on the Empyre new media arts listserv.

David Ost, a political scientist at Hobart and William Smith Colleges and my close friend from graduate school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, posted on the anniversary of the war’s end on Facebook. He argued that the war, which killed between one and two million Vietnamese, had the effect of “making the American government one of the worst mass murderers of the 20th century.” These deaths in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos—and in all the wars and epidemics that followed: El Salvador, Rwanda, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, Chile, Argentina, and forced migrations across the globe, as well as AIDS, H1N1, Avian Flu, Ebola, and SARS—live in all of us. These deaths surge through neoliberal greed, technocapitalist phantasms, and nationalist tragedies of both the pre-COVID and COVID eras.

And now, the COVID deaths: stories of people dying, alone. The question as bioartist and friend Kathy High has stated so eloquently is not when this will be over and gone, but instead, “when will we be living with the virus?”

What cracks and fissures will be exposed? To paraphrase Eduardo Galeano’s magnificent 1971 book Open Veins of Latin America: what are the open veins of the COVID virus?

Beethoven’s Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op 13 also known as Sonata Pathétique, composed in 1799, opens with a first movement in Grave (GRAH-vee). Grave holds the place of the slowest tempo in music: slower than adagio—heavy and solemn. It is the tempo for our souls enduring a crisis of proportions we cannot yet comprehend or navigate.

C minor is a key I love, for reasons that are hard to articulate. It is emotive, stormy, tragic, disconcerting. It is a key of tension and resolution, but also of struggle. C minor unsettles and opens up feelings and ideas hidden by the major keys. COVID, at least my experience of it both in my fears and on the screens and machines that define my life right now, performs in C minor.

COVID-19 works the scales and chords of C minor and pounds in the tempo of grave, GRAH-VEE as a solemn cadence, grave meaning serious, and grave as a place to bury the dead. Grah-vee, Grave, Graves.

If COVID breaks open the hidden veins of the pre-COVID world we all fought against in our art making, our teaching, our writing, then we might begin to play in the key of C minor.

We might have a chance to rest, recalibrate, reengineer, reimagine EVERYTHING: air, buildings, capitalism, classes, collectivities, death, disease, doing, economies, education, environments, feelings, food, genders, government, humans, ideas, identities, land, loving, nations, nonhumans, private, public, races, speaking, technologies, theories, thinking, writing, and PUBLIC HEALTH.

COVID has not just wrecked our bodies, our economies, our psyches and our well-being.

It has also unsettled, like the key of C minor, our art making, our disciplines, our research, and our theories. They are rocked and wrecked and shredded, like the dissonant chords in the Sonata’s first movement, separated by rests, syncopated, moving toward resolution but not yet finding it.

I Zoomed with my good friend and research assistant Julia Tulke, now sheltering in place in Athens, Greece. She had gone there to conduct her dissertation research on urban ruins of post-industrial collapse, comparing Detroit and Athens. She does ethnography, walking the streets and talking to people, but COVID upended and gutted her research. She can’t talk to people. Getting out into the streets is perilous. She now photographs COVID graffiti street art.

“You are tougher than you think,” Athens 2020. Artwork by EX!T, photo by Julia Tulke.

She is uncertain of the next step for her dissertation about two cities, both now dealing with the ravages of COVID. Her research plans are blown apart.

She talked to me about something deeply bothering her: the emergence of the COVID culture industry, with book proposals and CFPs and manifestos erupting from various prominent and emerging scholars weighing in on the virus, the pandemic, and every note of the current crisis. Is this COVID careerism a different yet insidious virus?

Julia pondered the ethics of this emerging trend: this idea that you can just take what you know, the theories you have swum around in for decades, and slap them on this catastrophe.

She said, “we do not yet know what we think about things. Everything we thought needs rethinking.”

And then we both talked about how everything is unresolved and that is the only thing we know. None of us is ready.

We all need time to marinate, to master the new dissonances, movements, notes, scores, tempos, tensions, and resolutions of COVID. It looms as a new sonata we have not yet learned to play because the key is difficult, the tempos erratic, and the chords complex.

My partner Stewart, who posted in mid-April in the Empyre forum, is a professor of public health at Ithaca College. With our son, we lived through SARS while teaching at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore in 2003.

Books on pandemics and health disasters from heat waves to AIDS to the drug wars to genocide to food insecurities spread through Stewart’s home study like kudzu. He receives many calls from various agitated friends and anxious relatives asking him what he thinks about the virus, when it will be over.

He will probably not like that I am quoting him, but I wrote this down after overhearing him on a Zoom meeting when I was drinking tea to fortify myself for grading papers for my remote instruction theory classes and programming our Rapid Response Salons on COVID-19 for the Ithaca College Honors Program.

Responding to someone who repeatedly asked what will happen, this former EMT calmly explained: WHAT WE KNOW IS THAT WE DO NOT KNOW.

The Sonata in C minor goes places we do not know.

I have played or more accurately, struggled with this piece for more than a decade.

I started to learn the sonata when I was recovering from reconstructive surgery after a trap door fell from a ceiling and smashed my nose and part of my face fifteen years ago. Bandaged, bruised, and recovering, I could not read books because I could not wear my glasses. So, I listened to opera and played piano.

The piece I sank into was Beethoven’s Sonata in C minor. Somehow, the unsettling chords, the grave, adagio cantabile, the rondo movements, the C minor key gave shape to my crisis and the traumas that I could not speak about.

Turbulence and discordance infiltrated my body, my damaged face, my dreams, my nerves. My face swelled from the surgery, where my nose had been rebroken with a mallet and the insides reconstructed with micro-size surgical tools. In fact, this is the first time I have spoken about the accident and reconstructive surgery publicly. The accident changed my breathing, my face, my nose, my programming/curatorial practice, my thinking, my writing, and my life.

Julia, Stewart, my accident, Beethoven, the key of C minor—these move me to assert: WE DO NOT KNOW WHAT WE THINK ABOUT ANYTHING ANYMORE.

And that might be the most ethical and political place to be, to question everything, to go deep into the cracks and the crevices and the fissures that COVID breaks open. We are in the first movement of this new sonata. The tempo is grah-vee, grave, in every layered and multiple meaning of the word.

Some of what we did before, the theories we took solace in, the writing we finished, the films and new media and artwork we made, must now change their function.

They remain as training workouts for the marathon of the COVID world that sprawls unknown before us. This newly forming world demands us to recalibrate, reimagine, and rethink everything: our bodies, our communities, our food supply chains, our futures, our interfaces, our platforms, our political commitments to justice and to others, our machines, our screens, our solidarities, our teaching, our theories, our work, and our writing.

In a recent piece entitled “Society after the Pandemic” for the Social Science Research Council, which she heads, Alondra Nelson urges scholars to bring our work out into the world and into conversation in the world. “Make it dialogic with the world it seeks to apprehend and improve. This is a time for creating knowledge pathways to a better world,” she concludes.

The confusion and turbulence of COVID: that is the place we all share now. It’s the first movement of the sonata, grave.

But most sonatas in C minor by any composer in any era, end with spirit and gusto. They do what Alondra Nelson advocates: they forge new pathways. They take us on a journey for which there are no words, and in the end, leave us elsewhere, a place we did not know.

We may start in grave, move through the flowing tempos of cantabile, but gather momentum in rondo, allegro, and forward movement.

So I end these five movements on COVID the way all sonatas end: with a movement that leaps with hope, lifting the body, the heart, the mind, the soul, the spirits in consort with phrasing and structures that suggest a way forward, if we can let go. IF WE CAN KNOW THAT WHAT WE KNOW IS THAT WE DO NOT KNOW.

I started this COVID Movement V with death. I end it somewhere else: in media, science, policy, and clear communication and in parody, art, music, and people.

I leave you with three grace notes: two that point to a new media world emerging and one that invokes human connection.

The First:

The daily press conferences of New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo (full disclosure: I am a huge fan), with their emphasis on facts, science, straight talk, and care for people. These pressers have accrued an international cult following. But they are not exempt from debate. Some colleagues critique Cuomo for cozying up to the cybercapitalists during the pandemic and also point to his poor record on prison reform. And then some friends will not Zoom, text, or talk on the phone when they air live at midday each day.

Art in America published a visual analysis of Cuomo’s excellent PowerPoints and the staging of the press briefings with everyone six feet apart in the majestic paneled room of the state capital building. A colleague extolled to me that every professor on the planet should study the Governor’s blue and gold PowerPoints for the clarity they bring to detangling complex concepts.

The Second:

The Randy Rainbow love song to Andrew Cuomo and his brother, journalist Chris Cuomo, now recovering from COVID. It parodies a song from the American musical, Grease. Rainbow’s parodies have a devoted cult following on Facebook and YouTube. Watch them when you need a belly laugh, a lift, and an injection of hope:

The Third:

A big thank you to Raza Ahmad Rumi and Sadia Abbas for pushing me to revise all of these pieces for a wider audience. A virtual hug to close friends and comrades Renate Ferro and Tim Murray in Ithaca, New York, who had the sheer guts to know that Empyre could open up a space for us to say together: WHAT WE KNOW IS THAT WE DO NOT KNOW

The Last Chord:

A huge, loud shout out of SOLIDARITY to everyone around the world sheltering in place and reading Ideas and Futures to find solace, community, and the power of the crooked story.

Together, we have shown irrefutably, irrevocably, and irreverently that ideas will get us through all of this.

“COVID Sonata in Five Parts” was originally written for the Empyre listserv as ‘Interfacing COVID 19: the technologies of contagion, risk, and contamination’ during April, 2020. Empyre- soft-skinned space is a global community of artists, curators, and theorists, who participate in monthly thematic discussions via an e-mail listserv.-empyre- has traced the emergence of new media theory, practice, and networked culture since 2002. This listserv is moderated by Renate Ferro, Junting Huang, and Tim Murray.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is Professor of Screen Studies at Ithaca College and Codirector of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival (FLEFF). Her most recent books include Thinking Through Digital Media: Transnational Environments and Locative Places (with Dale Hudson, 2015), Open Spaces: Openings, Closings, and Thresholds of Independent Public Media (2016), The Flaherty: Decades in the Cause of Independent Film (with Scott MacDonald, 2017), Open Space New Media Documentary: A Toolkit for Theory and Practice (with Helen De Michiel, 2018), and Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics (2019).