Patient care units, assembled by New York Army National Guard members and civilian staff, at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in New York City March 27, 2020. The convention center will be an alternate care site to ease the bed shortage of New York Hospitals as part of the state response to the COVID-19 outbreak (U.S. Air National Guard photo by Senior Airman Sean Madden)

by Patricia R. Zimmermann

OVERTURE

I would like to thank Renate Ferro and Tim Murray for initially encouraging me to share some thoughts on the Empyre listserv about the pandemic, the crisis, my life, and my work as COVID jolts everything I used to think and do into some new unknown.

I appreciated the opportunity to explore the personal, professional, and political on Empyre, as I rarely write in first-person or about myself. I was struck by how the pandemic has entangled the public and private, which are now much more permeable with Zooms into our homes and concerns about what public is or even means now moving forward.

I would also like to thank Raza Ahmad Rumi and Sadia Abbas, coeditors of Ideas and Futures, for inviting me to revise these initial listserv postings into a group of lyrical nonfiction essays structured in sonata form. I am indebted to them for getting this writing out into the world in a new way.

I play piano, which gives me sustenance, solace, and somewhere else to go, especially now. I have been working on some sonatas, picking my way through different moods and tones and movements; mistakes abound but it is the details of the notes that pull me in with the circle of fifths, dissonances, dynamics, harmonies, major and minor keys, mechanics, melodies, textures, and tonalities.

The more I play, the more these chords and lines enter my hands and heart. It is an elsewhere I relish because it is not a screen or a flat surface; it is about my hands putting something into space, even in all my fumblings and slowness.

My postings on Empyre were written in five movements, each at a different pace and tempo. I adopted this strategy because for me, shelter-in-place is not a narrative of Buddhist meditation and reading, or even a chance to increase my productivity.

Instead, quarantine jumps between moments of satisfaction from making dinner with what we have in our refrigerators and getting seminar papers graded, to the fear of dying alone, caught in an inadequate public health system.

I witness the divide between those who find this as a welcome respite from work and those who suddenly have no work yet have no respite because of financial precarity. And then, there are those whose work puts them on the front lines where their very survival is in question.

Every action and every emotion are entwined and snarled and changeable and unknown.

I start with Movement 1, Allegro.

MOVEMENT 1 ALLEGRO

After fifty-two minutes of calling, redialing, calling again, asking could you please get a phone to her? Is it possible for her to hear my voice? Just for a minute? I got my mother on the phone in her skilled nursing facility, and she could not understand me; her hearing aid had not been put in; she kept saying, I HEAR NOTHING NOT A THING I HEAR NOTHING NOT A THING.

On March 12, the Governor of the State of New York issued a decree that locked down all the skilled nursing facilities in the state. Overall, more than 40,000 nursing home residents have died nationwide, and some estimate that the actual number is much higher. As the death tolls in one facility mounted, the news showed workers in hazmat suits carrying out numerous body bags.

I had taken the day off from visiting my mother, Alice.

For the last five years since I moved her to Ithaca from Houston, I have visited almost every day.

This is not from Catholic guilt but because she has dementia, significant psychiatric challenges, can’t walk, mostly does not eat, and has been hearing impaired her entire life, categorized as legally deaf.

I visited her daily so she would have some human contact, some touching that was not medical, and some communication as she understands much better in person with slow talking and enunciation, reading lips like most people who are deaf or hearing impaired. She is ninety-six years old, the daughter of a coal miner and union activist who emigrated here from Scotland.

It was our Spring break at Ithaca College. I had settled in for a day—a luxurious day—of staying at home, reading and writing, without any pressure to get into my blue Volvo to visit. But that announcement did away with my autonomy. The governor was closing the nursing homes and assisted living facilities across the entire state in a matter of hours. Lockdown.

I rushed over to Oak Hill Manor on Hudson Street. The parking lot was a jumble of cars double parked. Families poured out in groups, carrying stuffed animals, plants, flowers, blouses, packages of Oreo cookies. I found the last parking spot overlooking an elementary school playground.

I entered the nursing home and was surrounded by two aides. One took my temperature. It was fine. The other squirted hand sanitizer into my hands and said she had to watch me apply it. Families streamed in with children, with cousins, husbands, wives, brothers, sisters. I was the only person there alone.

A nurse was training aides in how to properly wash their hands: first get the thumbs, do the back of the hand, do the finger tips, suds up, twenty seconds, two rounds of Happy Birthday. One of the aides did not meet the standard and was directed to start over.

I observed three different rooms where staff were interviewing young women of color to be aides. The doors were open, no privacy, just interviews. I saw two young women with tattoos, one with purple hair, the other with braids, filling out job applications in the visiting room where residents often sat in their wheelchairs, talking to their family members and looking out at the trees.

Nurses, doctors, aides, staff members, family members, job applicants, and receptionists swarmed and buzzed around the facility. Nursing homes are usually not places of energy, but places of quiet, sadness, and isolation. This was different. Allegro. Speedy.

I passed the temperature test and the hand sanitizing test, signed in, and then walked down the hall to my mother’s shared room. Almost every room was filled with visitors, more than I have ever seen there before. Hardly anyone visits nursing homes, they are lonely places with people whose minds are living in other distant fragmented worlds.

I heard crying. I heard moaning. I heard screaming. I heard questions asked over and over. I heard the word WHY WHY WHY WHY bursting out of a room. These were the residents, most of whom were living with some form of cognitive impairment, trying to process all the commotion, all the visitors. The coronavirus was not something they could easily understand.

I went to see my mother. She was lying in bed. She kept repeating: what is going to happen to me, what is going to happen to me? Given her executive function impairments, I had decided not to try to explain that she would be in lockdown and I couldn’t visit for an indefinite period. I turned on CNN, hoping that the news of the coronavirus might give her a hint, but it made no sense to her. WHAT IS GOING TO HAPPEN TO ME, WHAT IS GOING TO HAPPEN TO ME?

An aide who speaks often with me gave me her private mobile number, which is against the rules. I left. I went to my car, sat in the driver’s seat looking at the playground and wondered when or if I would see my mother again. I had given her a long hug, realizing that she could die before the lockdown ended. The nurse told me that they had been hoping that if end-of-life were near, one family member in full medical suiting could sit with the person. Now, I understand that will not be possi

Sitting in my car, I could not feel or think. One horrible thought rippled through me: how will she hear and who will take care of getting her nanotechnology hearing aids in so she can be a little bit in the world and not live totally in the floating shards of her memory?

The social worker called me a few hours later. She said Governor Cuomo was shutting down the homes for a month, but I knew that was not true. One of the nurses, whose name I do not even know, pulled me aside into a little alcove. She whispered: I’ve been talking to a friend in Washington state, out West. And to a friend who works for the state of New York. This is going to be longer than a month. Long. Not sure how long. Steel yourself.

I send my mother simple letters every day, epistolary meditations about the daffodils, the split pea soup I am making, my son out in Santa Monica who now paints and bakes bread when not doing his work in the tech industry.

People are horrified when they hear that my mother is in lockdown and I can’t see her. They’re so glad that their parents live in their own homes and can use FaceTime and Zoom. They tell me that my situation won’t be so bad if I just have her install Zoom and call me on Face Time.

The thing is, my mother is in an advanced state of cognitive and psychiatric decline and cannot even dial a phone herself, much less use the apps that my friends and some relatives recommend. I can call her, but because she is also deaf, she needs to see me to read my lips. In short, there is no digital solution available to allow us to communicate. Without in-person visits, she’s isolated, adrift with no ballast or anchor.

A family member, who is so happy that her parents are in their home and can see their children and grandchildren with these myriad apps, found my story, as she put it, “heartbreaking.” It is not. It is the reality of COVID, where I must live in the moment, knowing that if I do not get a call, COVID has not visited my mother in the nursing home, and she is still alive. Stories of virtual birthday parties and graduations, of digitally-rendered closeness, do not comfort me.

In the first two months, I spoke to my mother for a total of eight minutes over three times. Each call required three or more days to organize and set up, but my feminist politics will not let me get angry.

The nurses, aides, and staff are overworked, scared of COVID, without sufficient PPE, dealing with the immobilized and cognitively impaired, the most high-risk population.

On one of my attempts to call, I asked the nurse how she was doing. She said, I need to be honest. I’m doing badly. It’s so intense here. There are not enough workers and aides and nurses because every patient needs to be completely isolated. We need more PPE. We wash our hands constantly. We don’t know where COVID is but we know if it comes, there will be death.

I am ready to lash out if I hear another person suggest FaceTime, Zoom, Skype, laptops, iPads, or mobile phones as a way to help my mother. For a person with dementia and deafness, any of these devices is challenging or downright unworkable, and all of them require staff who are stretched impossibly thin to take time out of caregiving to help the person use it.

I have noticed that so many in this crisis see technology—particularly digital technology—as a salvation, a vaccine against the horrors of COVID and isolation, a displacement of their existential fears of the unknown and death into a machine, a keyboard, a surface.

Nobody asks me how I am doing or what I am feeling. How does one deal with lockdown of a deaf and demented ninety-six-year-old who can’t understand what is happening in the world. WHAT IS GOING TO HAPPEN TO ME? WHAT IS GOING TO HAPPEN TO ME?

I remain happy with the thought that my partner and I took her to Boatyard Grill on the south end of Cayuga Lake the Tuesday before for her birthday. We shared steamed fish and asparagus, and she blew out a lone candle on a piece of key lime pie.

Alice Rodden Zimmermann, born March 9, 1924, in NY Governor Cuomo mandated lockdown since March 12, 2020.

Six days later, reading endless praise for all the new technology available to faculty in the Roy H. Park School of Communications to teach our classes in a normal way to maintain continuity, I have had it. SUBITO. FORTISSIMO. I lash out, arguing that technofetishism disguises a work speed up, and the idea that there can be normal classes is an insufferable pretense. Nothing will be normal. We are in crisis, and death.

I thank my mother for teaching me this: that although nanotechnology hearing aids gave her some contact with the world, digital technology is a chimera of connection and cannot ultimately resolve her isolation—or ours.

When I make my argument to colleagues in the Park School who are arming themselves with various new programs, I thank my mother whose lifelong deafness and late-life question WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO ME WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO ME gave me the insight that technofetishism will not get us through this crisis, will not give us calm, connection, touch, or lips to read.

All of this unfurled in allegro, a steady pace, with forward propulsion, confusion, loss, unknowns, and mourning.

COVID-19 MOVEMENT II: ADAGIO

We canceled the proposed Virtual Reality (VR) salons in mid-February.

I am the codirector of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival (FLEFF), now in its 23rd year. I love this job.

Slowness marks my theoretical and historical scholarly work. Festivals work in the opposite tempo: fast, changing, adapting, responding, intervening, infiltrating, and convening.

While as a scholar I write alone, as a programmer I collaborate on so many levels and with so many people, I can’t even list them. So my appointment at Ithaca College navigates a contradiction between slow and internalized entwined with fast and externalized. Control on one hand, kayaking the rapids on the other.

I watched our programming, conceived and executed over a year, slowly disintegrate, like water slapping against sand on a beach.

They were the first cancellations of what would be a cascade of disappointments. Our festival theme this year is INFILTRATIONS. Apt? Prescient? Eerie? Creepy? It all happened slowly, like the second movement of a symphony where after the rollicking opening movement, the pace abruptly drops down, the key changes, and a new mood arises in contrast.

Artwork for Infiltrations, the 23rd Finger Lakes International Film Festival, originally scheduled for March 23-29 2020.

Tom Shevory, my codirector of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival, had collaborated with VR artist and activist Liz Miller from Montreal for over a year. Matt Holtmeier from Eastern Tennessee State University was also on the team. Tom had bought a headset in anticipation. He and Liz were figuring out various VR projects. He had figured out how to mount a VR salon in a campus seminar room. The festival would run March 23-29, with VR on campus and also downtown at our local art cinema, Cinemapolis, a key festival partner.

For a year, we had picked apart the public health issues of VR headsets at festivals. We learned about a problem at Sundance, where twenty people from one lab all contracted conjunctivitis. We analyzed how MASS MoCA cleaned their headsets. When attending the Festival du Nouveau Cinema in Montreal in Fall 2019, I went to two VR exhibitions, taking notes on the disinfecting process: alcohol wiping of all surfaces, the attendant wearing surgical gloves, rules that headsets could not be shared.

In January, we read about Wuhan. Then, in February, Seattle. Finally, a viral spread no one had ever seen before. As an environmental film festival, we devour news about land, soil, health, war, migrancy, and disease.

Tom and I chatted quickly on the phone. We decided that with the outbreak, there was no way we could keep the headsets safe. We canceled the VR salon. I informed the interns. No VR. Not safe.

Then, we talked about how to maintain public health in a movie theater and then in a concert hall. An administrator told us to buy up gallons and gallons of hand sanitizer and have it all placed prominently in Cinemapolis, the movie theater. In late February, we could not find any. I was bringing Lysol wipes to my classrooms to swipe keyboards and desk surfaces clean.

We decided on a new protocol: staff and interns would not shake anyone’s hands at the festival.

A VP with whom I’m friendly took me out to dinner to discuss how to leverage the festival for Ithaca College. It was March 4. She said, don’t worry, the college is shutting down all large events over one hundred, but FLEFF, although large, aggregates many small events.

From March 5 on, Tom and I could not focus. We went through the motions of tweaking the timing of films at the theater, master classes, salons, and hotels for guests. Every day we spoke on the phone: will we be canceled or continue with smaller gatherings? It was almost impossible to fire up the energy to attend to the myriad details of a festival two or three weeks before it launches. Designs for programs and PowerPoint slides were still coming back for feedback from our designer. I simply could not concentrate at all even though I made list after list of details.

Tom and I followed the entertainment trades closely. We asked other festival directors what they were planning to do. Some said they were moving totally online to various platforms. Some said they were just canceling. It was a slow, arduous process of emails, phone calls, moving slowly, trying to figure out what to do and knowing our decisions were not our own because of the way they affected others.

We also wondered how does one have a festival, which produces fun and community as well as art encounters, during a virus like this?

SXSW canceled and let go enormous numbers of staff. Then, the Environmental Film Festival in the Nation’s Capital. We chatted on the phone: with these two cancelling, we knew that everything we had worked on for a year would slow down and then disappear. Slow. Slow. Then done. Over.

The administrator in charge of FLEFF, Dr. Tanya Saunders, called on a Monday afternoon, March 9. The Provost decided to cancel FLEFF, saying it was too large. I spent the night unable to sleep, but I was relieved in some crazy way, as the burden of navigating a public health crisis of unknown proportions and impact at a festival lifted. I was also sad that a year of work had evaporated, gone with one phone call. But festivals constantly adapt and morph. We knew the programs could slide to 2021.

Tom and I were both relieved not to bear the responsibility for the health of others when nobody seemed to understand the disease. The image of coronavirus, the red ball with the spikes that was ubiquitous on the news and social media, irritated me. It presents as a scientifically accurate image, but it is actually a stand-in, an emblem, a placeholder for the unknown.

I had to cancel at least eighty-five guests: musicians, performers, filmmakers, new media artists, scholars, and moderators. It might have been even more than that. I felt awful telling the local art cinema we were canceling, as FLEFF brings in not only large crowds but generates financial resources. It’s the biggest box office of the year for the theater.

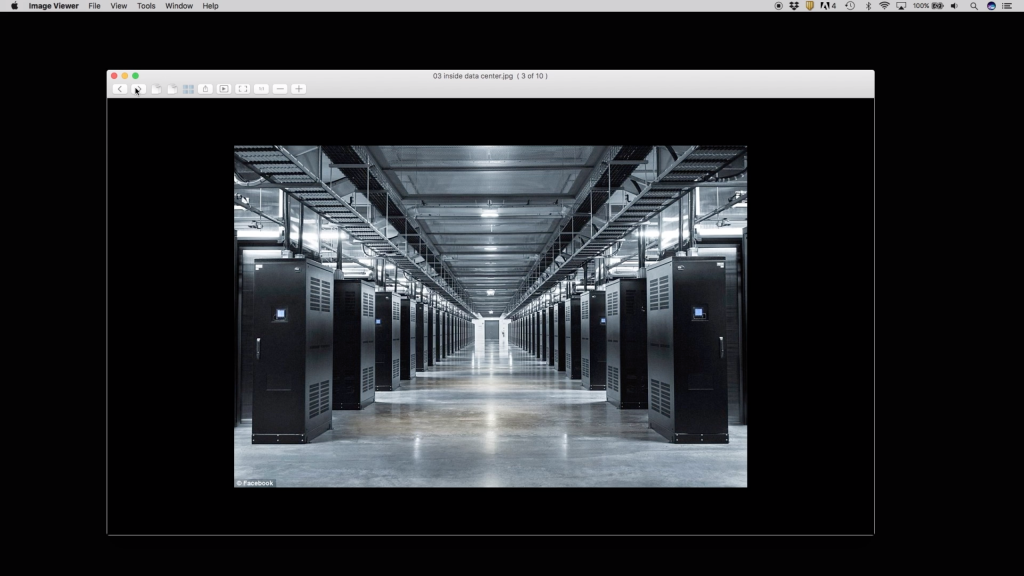

The methodical deductive thinking of curatorial work occupied our thoughts. It is slow work to respond, as moves must be given sufficient consideration. We asked our digital curators, Dale Hudson at New York University Abu Dhabi and Claudia Pederson at Wichita State University, if their Radical Infiltrations new media exhibition could be moved up and go live. I spent hours loading it. Dale spent more slow time adapting the essay for the films. The exhibition, Radical Infiltrations can be viewed here.

Still from Roger Beebe’s “desktop cinema” essay Amazonia (US, 2019), winner of a jury prize at FLEFF Radical Infiltrations New Media Exhibition.

We decided we needed to do more. Many listservs for media studies faculty of all persuasions, areas, and methods exploded with requests for online material. Most faculty had only a week or so to move to remote instruction. And not every school boasted the large library staffs like the one we have at Ithaca College who can digitize titles.

Our festival cut line is FLEFF: A DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENT. We collaborated with the Park Center for Independent Media to mount an exhibition of online analog short videos and some interface projects like Coronavirus Dashboard in an exhibition entitled INFILTRATIONS: A DIFFERENT MEDIA ENVIRONMENT.

In our slowness, which felt like walking through water in an outdoor pool on a cold, windy day, we decided to play on the original title. The exhibition includes community media from groups like Scribe Video, COVID-related pieces from Indonesia and the Philippines from EngageMedia in Indonesia/Thailand, disability rights work from Insights International, Indigenous media of resistance playlists from Cinema Politica in Montreal, and the experimental videos of Wenhua Shi. You can see the exhibition here, and even use this work for your remote teaching to fill in the holes left from moving online.

Still from “Manila’s Poor Under Lockdown,” EngageMedia, April 1, 2020. https://video.engagemedia.org/view?m=R1WFKNK9o.

Cinemapolis needed to shut down.

As Board members, Tom and I were pulled into a meeting to figure it out. I suggested that my partner Stewart, a professor of public health, be brought in. We closed but committed to a fundraising campaign so the employees could earn their salaries. Within four days, the community donated sufficient funds to cover one month. Slowness defined this process, slow deliberations, thinking through every corner and angle, every implication, the impact on low- wage workers.

In April, Brett Bossard, the executive director of Cinemapolis, approached us. Independent film distributors like Kino, Icarus, Oscilloscope and more were offering a new idea: Virtual Cinema. The current release could be on the theater’s website. You clicked a link and paid $12. The money was split 50/50 between the distributors and Cinemapolis. That way, the theater could earn some money and the release could get out to the public.

Brett noted that eleven of the titles we had programmed for FLEFF were available from these boutique distributors, including Bacarau (Brazil), White White Day (Iceland), The Whistlers (Romania), Cordillera of Dreams (Chile), Dying for Gold (South Africa), and more. You can see these films here.

$12 dollars a view, good for five days!

We said let’s do it, let’s try it, let’s start slow, with a few titles. Let’s promote it in a slow methodical way. Let’s get these films out into the world for whatever audience is left. Let’s slowly see if the art film and festival audience will do this, if they are sick of Tiger King and Netflix bingeing, and want to immerse, slowly, in something denser, more nuanced, with cinematography that is not shot in thirds with a closed-frame composition. You don’t have to live in Ithaca to watch. You can support local art cinemas everywhere while you are slowed down.

If you are in your home, you can see the world through your screen.

Watch digital art and community media online (through FLEFF and through other initiatives), because these works give us all a break from escapist mainstream media and vaccinate us against the virus of transnational capital.

Watch films that are not shot to center characters in the middle of the screen and edited to enter your synapses and alter them for the networks of global capital.

Watch films that with each click of the keyboard slowly, incrementally, save cinema and save our senses from the barrage of the American-centric, the easy-to-digest. Supplement your Amazon and Netflix bingeing with these films. Mix art films with popular culture viewing to experience a richer, more complex media ecology.

We all need to give ourselves some respite from the incessant harassment of commercial media culture that pounds our hearts and brains into dust.

We all need to save ourselves from the fast pace of CNN and Netflix with the thoughtful and deliberate speed of new media art, community media, political and activist works, and art films in Virtual Cinemas.

None of what I elaborate here was done fast.

This moment fills us and humbles us. It demands detangling, new routes, methodical thinking, listening, absorbing, knowing we must get it right but will probably get it wrong. Bravado fades and with it, interventions disintegrate.

What remains are slow infiltrations and recalibrations, constant listening, watching, and small adjustments.

Slow. Adagio.

“COVID Sonata in Five Parts” was originally written for the Empyre listserv as ‘Interfacing COVID 19: the technologies of contagion, risk, and contamination’ during April, 2020. Empyre- soft-skinned space is a global community of artists, curators, and theorists, who participate in monthly thematic discussions via an e-mail listserv.-empyre- has traced the emergence of new media theory, practice, and networked culture since 2002. This listserv is moderated by Renate Ferro, Junting Huang, and Tim Murray.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is Professor of Screen Studies at Ithaca College and Codirector of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival (FLEFF). Her most recent books include Thinking Through Digital Media: Transnational Environments and Locative Places (with Dale Hudson, 2015), Open Spaces: Openings, Closings, and Thresholds of Independent Public Media (2016), The Flaherty: Decades in the Cause of Independent Film (with Scott MacDonald, 2017), Open Space New Media Documentary: A Toolkit for Theory and Practice (with Helen De Michiel, 2018), and Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics (2019).